Porcelain

The word 'porcelain' is derived from the old Italian term 'porcellana', meaning 'little pig', which was the name for the cowrie shell, whose translucent, shiny white surface has the appearance of porcelain. The cowrie shell was named 'little pig' as its furrowed opening was considered to resemble the vulva of a sow. Following the discovery of porcelain in China, where it is known as 'ci' 瓷, the volume of production and export of porcelain lead to the name 'China' becoming synonymous with the wares since the name of the country of origin was written on the shipping containers.

While it has broad appeal, porcelain is a challenging material to work with. In the book Porcelain by Vivienne Foley the author states that

"...porcelain is a notoriously demanding medium that presents unique challenges for the maker."

I have found that porcelain requires great care to be taken in all stages of the ceramic process: forming, drying, glazing and firing if one is to have any degree of success with this challenging material.

However, porcelain has unique properties which, despite the challenges, make it very appealing for the construction of both functional and sculptural work.

Origins of Porcelain

In Chinese Glazes by Nigel Wood the author says that the discovery of porcelain in China

"...seems to have happened more or less simultaneously at a number of southern kiln sites where greenwares were made, and sometime in the early 10th century AD. The important southern kiln complex of Jingdezhen was among the first in China to exploit this important new material."

Porcelain with carved decoration under celadon glaze

Jingdezhen ware 19th century

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The author goes on to say,

"By the time true porcelains first appeared in the south ... white porcelains had already been manufactured in north China for more than 300 years."

However, following repeated attacks by invading tribes northern porcelain production went into decline.

He describes the true porcelains as being

"...lower in the colouring oxides of iron and titanium, and also somewhat richer in the flux-rich mineral hydromica. These small but vital differences made the southern porcelains white-firing and translucent, while the old southern stonewares were greyish and opaque."

"Once deposits of pure porcelain stones had been identified by the potters, white porcelain production sprang up at many kilns throughout south China in the 10th and 11th centuries..."

Jingdezhen, a city in northeastern Jiangxi province, became the largest centre for the production of porcelain in China.

Origin of Southern Ice Porcelain

Southern Ice Porcelain was formulated in Australia by Les Blakebrough (1930-2022). For a research project in the 1990s Blakebrough analysed a range of types of kaolinclay, examining plasticity, shrinkage, warping, iron content and translucency in an effort to produce a world class porcelain. He states,

"Gradually, after endless testing, our own material gave results better than imported counterparts".

He named the clay 'Southern Ice' for its qualities of "whiteness of snow and translucence of ice".

https://www.anbg.gov.au/biography/blakebrough-les.html

Whiteness

Southern Ice porcelain is white when fired in oxidation, but can take on a subtle blue tone when fired in reduction.

Firing

Clays are formulated to mature within certain temperature ranges; Southern Ice porcelain is typically fired to 1280 - 1300 °C (2336 - 2372 °F) or cones 9 - 10. However, firing to such temperatures and beyond can place stress on the ware sometimes causing cracking or warping, particularly if the heating and cooling stages are not carefully controlled. The pale blue ikebana vase below requires a dedicated support during the firing or the broad rim will slump.

Ikebana Vase with Qingbai Glaze

Colour Response

The whiteness of the body faciltates a very clear colour response to the colorants in the glaze as porcelain contains negligible amounts of iron in contrast to other clay bodies. Glazes react with the clay body during the firing and a clay which contains iron will muddy the colour. This is particularly true with lightly tinted transparent glazes such as celadons - the colour may be overwhelmed on an iron-rich clay body to the extent that no colour is apparent or the glaze appears dark olive green or brown.

Glazes for Porcelain

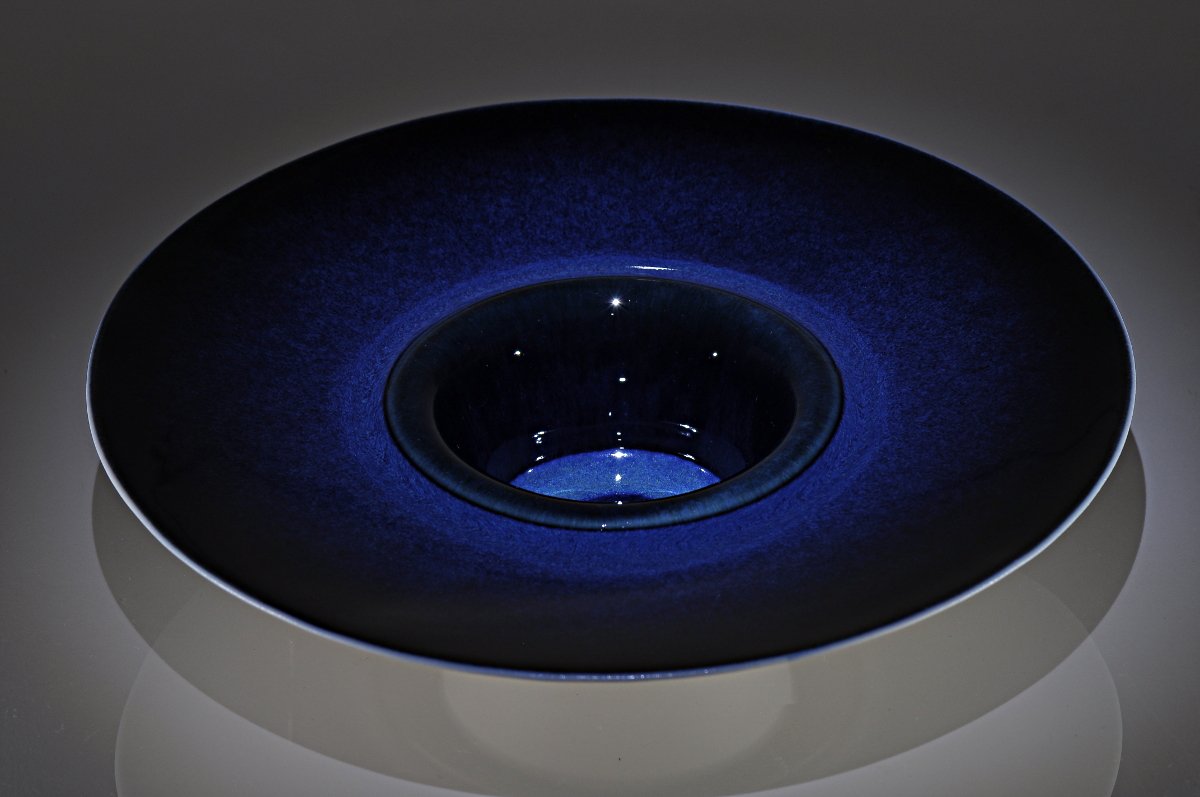

Classic combinations of porcelain and glaze include celadon, qingbai, jun and copper red fired in reduction with the clearest, most vibrant colours often occuring on true porcelain bodies.

As the glaze melts and fuses onto the surface of the body there is an exchange of materials between the clay and the glaze and this will affect the final appearance of the piece. Many glazes appear richer and more vibrant on porcelain than on other clay bodies. Some glazes such as crystalline glazes are best fired on porcelain as an overload of alumina absorbed into the glaze from non-porcelaneous clay bodies inhibits the fluid growth of the crystals or causes too many to form.

Celadon

If a transparent feldspathic glaze is fired to 1280 - 1300 °C in the reducing atmosphere of a gas or wood fired kiln a pale green or blue may be obtained if there is small percentage of iron (0.5 - 2%) in the glaze, or if there is some iron in the clay body or slip. The same glaze fired in oxidation would produce a pale straw or honey-coloured yellow. Celadon is a name used to describe both a pale green transparent glaze and also the ware, such as Longquan celadons. It is thought that celadon was highly prized for its resemblance to jade, a very valuable material in ancient China. The word 'celadon' is European in origin, but there are different theories regarding its source.

Obtaining a pale blue is more challenging and requires that the glaze ingredients, (e.g. potash feldspar and kaolin), are very low in titanium. As Nigel Wood notes, true porcelains are "...lower in the colouring oxides of iron and titanium", thus such porcelains glazed with materials specified above can produce the pale blue colour seen on the tripod sake cup by the author and on the work by Tsubusa Kato below.

Southern Ice Porcelain

Qingbai Glaze

Note, in the following section I include Chinese and Japanese characters so these may be cut and pasted into a Google image search. For example, pasting the Japanese expression 青白磁 'seihakuji', (pale blue porcelain) into a Google image search will locate images of work by artists such as Tsubusa Kato, 加藤委, and Fukami Sueharu, 深見陶治, who are major Japanese exponents of this medium.

The Chinese character for porcelain is 瓷, pronounced 'ci', but this is used to refer to any white porcelaneous stoneware, not necessarily translucent. The Chinese expression for 'celadon' is 青瓷, qing ci (green porcelain). A paler glaze with a greenish blue tone and also a type of ware is qingbai 青白 qing bai (green white). Note that the first character in celadon and qingbai is the same - 青, qing, which can mean green, but also blue in some Chinese expressions such as 'blue sky' - 青天 qingtian.

Thus, the colour of a transparent glaze containing a small amount of iron and fired in reduction may appear as green or blue, and may be referred to as celadon or qingbai, but the term 'celadon' is frequently used in English to refer to a range of hues. A Google image seach on the two terms, 青瓷 - celadon, and 青白 - qingbai, will illustrate the range of colours and wares. The Japanese word for celadon is 'seiji' 青磁, while a pale blue glaze is referred to as 'seihakuji' 青白磁.

To differentiate between the two colours, derived entirely from dark red iron oxide, which I use in my work I use the term 'celadon' to refer to transparent green glazes and 'qinqbai' to refer to a blue glaze.

Glazes may flow more on porcelain than on other clay bodies - as with any glaze it is important to test it on different bodies in a variety of firing conditions to achieve the best results. Some ceramic artists, such as Tsubusa Kato, utilise this quality of flow in their work where thick drips of molten glass are frozen like icicles hanging from the forms of their works.

Glaze flow on porcelain

Translucency

True Porcelains such as Southern Ice are translucent if the walls are suffiently fine and are unglazed, or glazed with a transparent glaze. This property lends itself well to the interplay of light, which enhances the depth of a transparent glaze. This quality was exploited in the finely carved Chinese wares where transparent glazes delicately coloured with oxides of iron created a feeling of great depth over carving that was perhaps merely 1 to 2 millimetres in depth, the glaze pooling in the recesses and the slightly thicker glaze appeared slightly darker.

Strength

The translucency and apparent delicacy of porcelain belie its strength: it is stronger than stoneware bodies fired to similar temperatures. During firing the silica melts, mullite crystals are formed and the other minerals in the porcelain body are fused into a glassy matrix in a process known as vitrification. This process imparts great strength to the porcelain.

Many extant works in private collections and museums are hundreds of years old; however, their provenance in imperial households throughout the centuries would have helped ensure their survival.